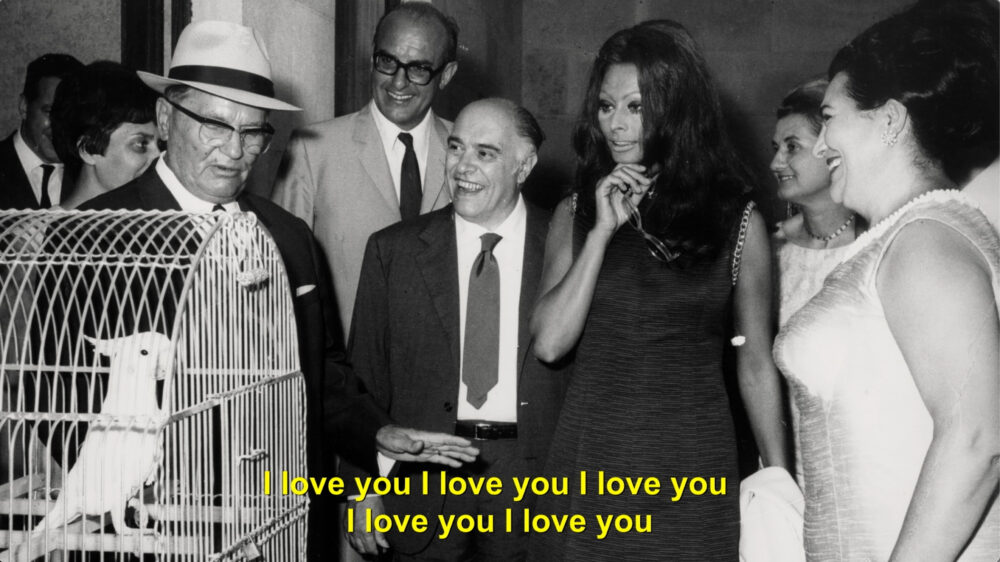

Koki, Ciao

Co-written, narrated, and featuring sound effects by Koki, a 67 year old speaking cockatoo formerly owned by Tito, president of Yugoslavia, Koki, Ciao is a short experimental documentary and autobiography, featuring a non-human as its central creative figure.

Collecting previously unseen footage and images from state archives, the film weaves together fragments of Koki’s life on Brijuni Island, Tito’s late residence, where he was witness to state visits from political figures, such as Nikita Khrushchev, Sukarno, Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu, and Robert McNamara, during formative moments in the Non-Aligned Movement, as well as Hollywood figures such as Sophia Loren, Orson Welles, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, who represented Tito on screen. Today Brijuni is still home to animals who arrived as symbolic gifts to Yugoslavia, and it’s from here Koki is displayed to crowds of tourists from a cage.

11:10mins, 1.78:1,

DCP 2K, 5.1 Sound

Here I am, writing you a letter. **

Thank you for the flowers. **

The whole room is saturated with their fragrance; **

I hated so to leave them that I didn't go to bed. **

In this absurd room with its columns, its weapons and its stuffed owl, **

I feel at home. **

The warmth, the smell, the peace and quiet belong to me. **

I take them with me like a reflection in the mirror: **

When I leave, they leave. When I return, I look—and there they are. **

I can hardly believe that they live in the mirror only through me. **

Now I wish most of all that it were summer, **

that everything that has happened had not happened. **

That I were young and strong. **

Then, perhaps, of this cross between crocodile and child **

would remain only the child and I might be happy. (ET) **

Speculative Facts

The Department of Speculative Facts connects two seemingly contradictory approaches: Speculation which attempts to think and act beyond existing knowledge and structures, and fact checkers in search for a solid consensus on which our reality can be built. When stretching knowledge and speculating with fiction, what sense of responsibility is needed in times of democratized opinions and fake news? Learning from the other SF—Science Fiction—we think of speculation through facts, and facts through speculation, to situate ‘truth’ culturally.

Collaboration with Lietje Bauwens and Karoline Świeżyński

“A fact, at its base, is a kind of social contract.”

** Or so concluded one contemporary expert on facts—professional fact checker Alex Carp.

** Reviewing factual claims by journalists on a daily basis for The New York Times Magazine,

** he saw cracks in the once-held belief in facts, as an objective, rock-solid ground on which our political, scientific and social reality can be built.

** To tease out this alleged social nature of facts, we asked Carp and his colleague Jamie Fisher to discuss their profession,

** which took place via an e-mail exchange.

** Weren’t fact checkers supposed to be the rational answer to irrational times?

** What can we learn about the politics of facts when such apparent guardians of truth flirt with post-truth ideas?

** We observed that many artists and writers working with similar questions about the social nature of facts tend to a more speculative approach.

** By including contingency and the unknown, it becomes possible to construct alternative futures that are more emancipated than our current present.

** Yet as much as speculation is necessary for producing new political strategies and imaginaries,

** it also has the potential to erode even more trust in institutions, governments, and perhaps social life itself.**

The Department started out of the neologism ‘Speculative Facts’

** to express our concern about this friction between two separate terms

** that seem both loaded and at times contradictory.

** We decided to think speculation through facts, and facts through speculation, by bringing them together in one concept,

** with the idea of finding new types of ‘social contracts’ with which we can anchor ourselves.

The Trial

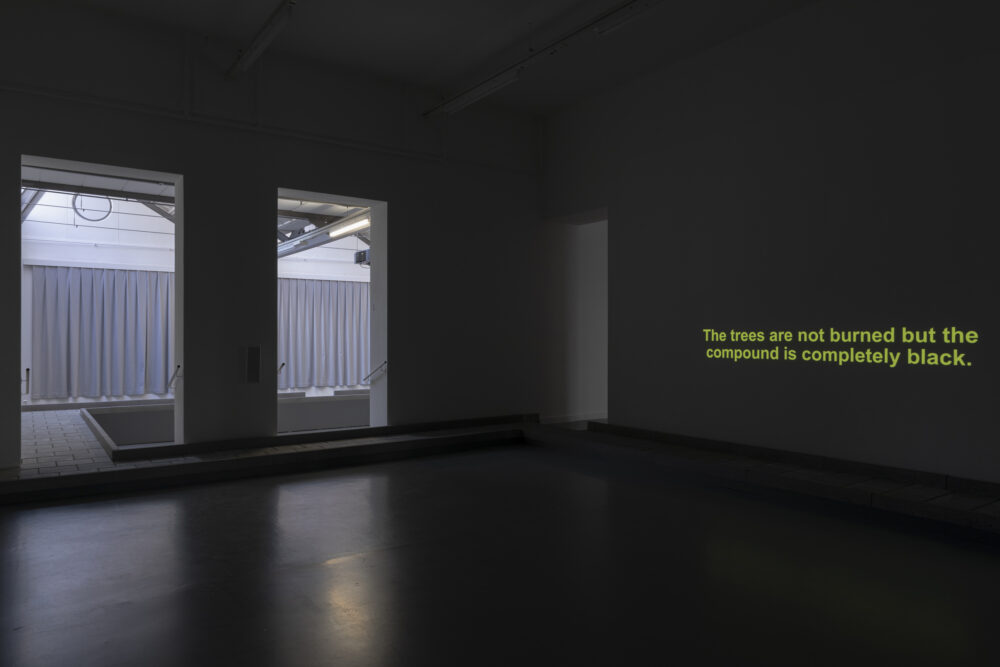

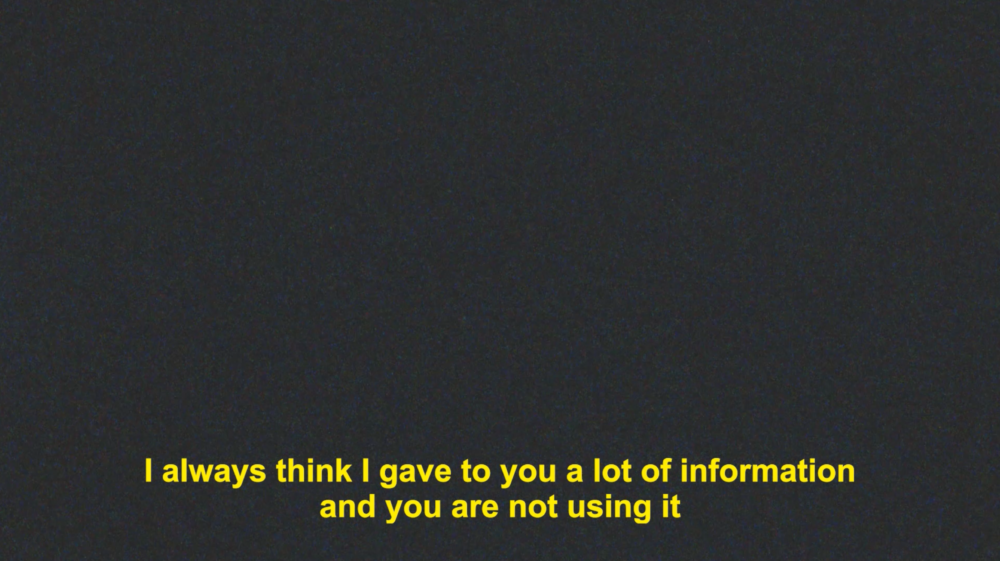

The Trial is a body of work made with employees from the International Criminal Court’s Investigation Division. Within the court’s structure, the investigator cannot control the way the research she produces will be read, which is done by a separate legal department acting within a jurisdiction that’s often opaque or an instrument of colonialism.

The office, evidence, processes and software used are not directly accessible, but the investigators reconstruct them with spoken descriptions. As they talk, transcribed subtitles appear which interrogate the relation between their memories and conclusions in the realm of law.

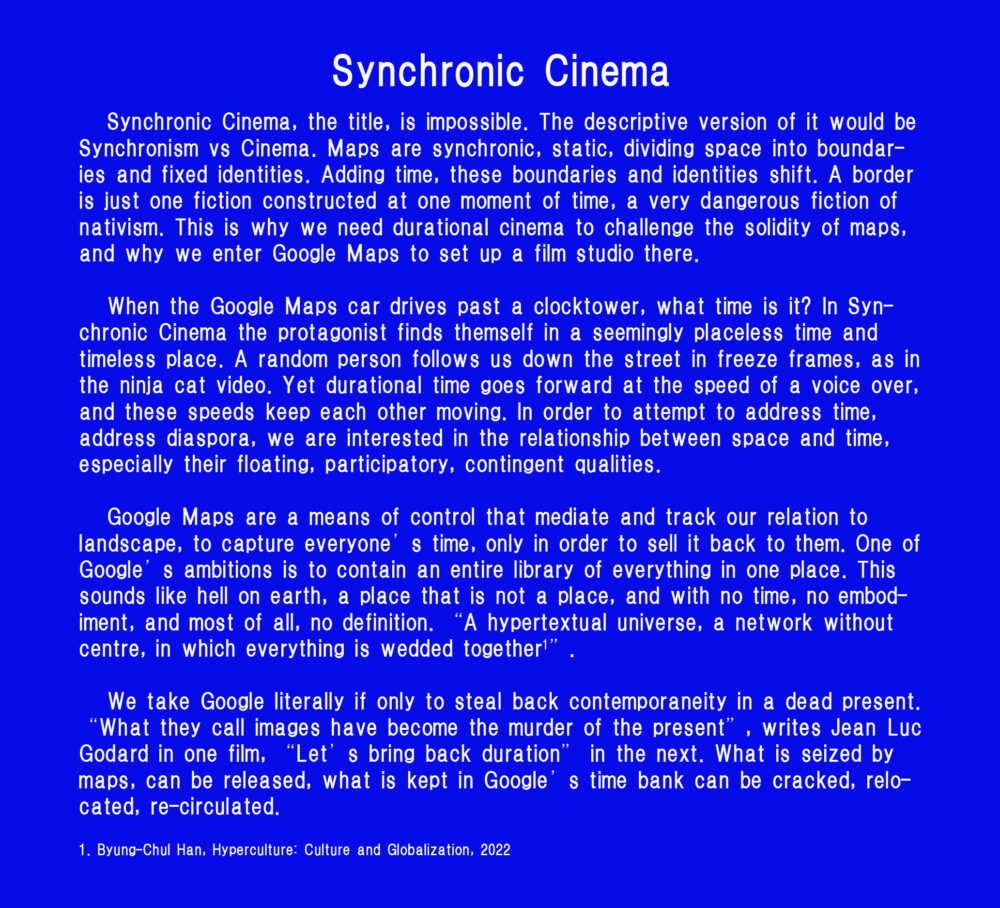

Higher than History

Public event and film shot at 1000fps, Gent, 2021. Produced by 019, Smoke and Dust, FMX Forever, Publiek Park, flag by Anthony Ngoya, texts over the PA system by Lindah Leah Nyirenda and Harun Morrison, supported by SIGN Groningen, Young Friends of the S.M.A.K, Camuse, Citadel Park and the Flemish government.

![]()

In myths there is no time, everything is fixed in place.**

The two men in this sculpture were made to hold a street light, and electricity – power – was a symbol of socialism **

and the sculptor, Julius-Pierre Van Biesbroeck made work for the socialist movement. **

When the sculpture was completed in 1902 Van Biesbroeck received a message:**

A mistake had been made! A light post was infrastructure not art, and was not eligible for the public funds for monuments.**

Yet if it was holding a flag he could be paid more than the regular cost of a lamp post.**

Julius-Pierre Van Biesbroeck was furious but said yes, if his work could be raised off the ground on a mound of dirt. **

The meaning of this mound is open ended, but anyway, he needed the money.**

The two near nude figures rub up against each other as they jam their big pole in the ground.**

No matter what it is they desire, electricity, nationalism, colonialism, a myth stays affixed.**

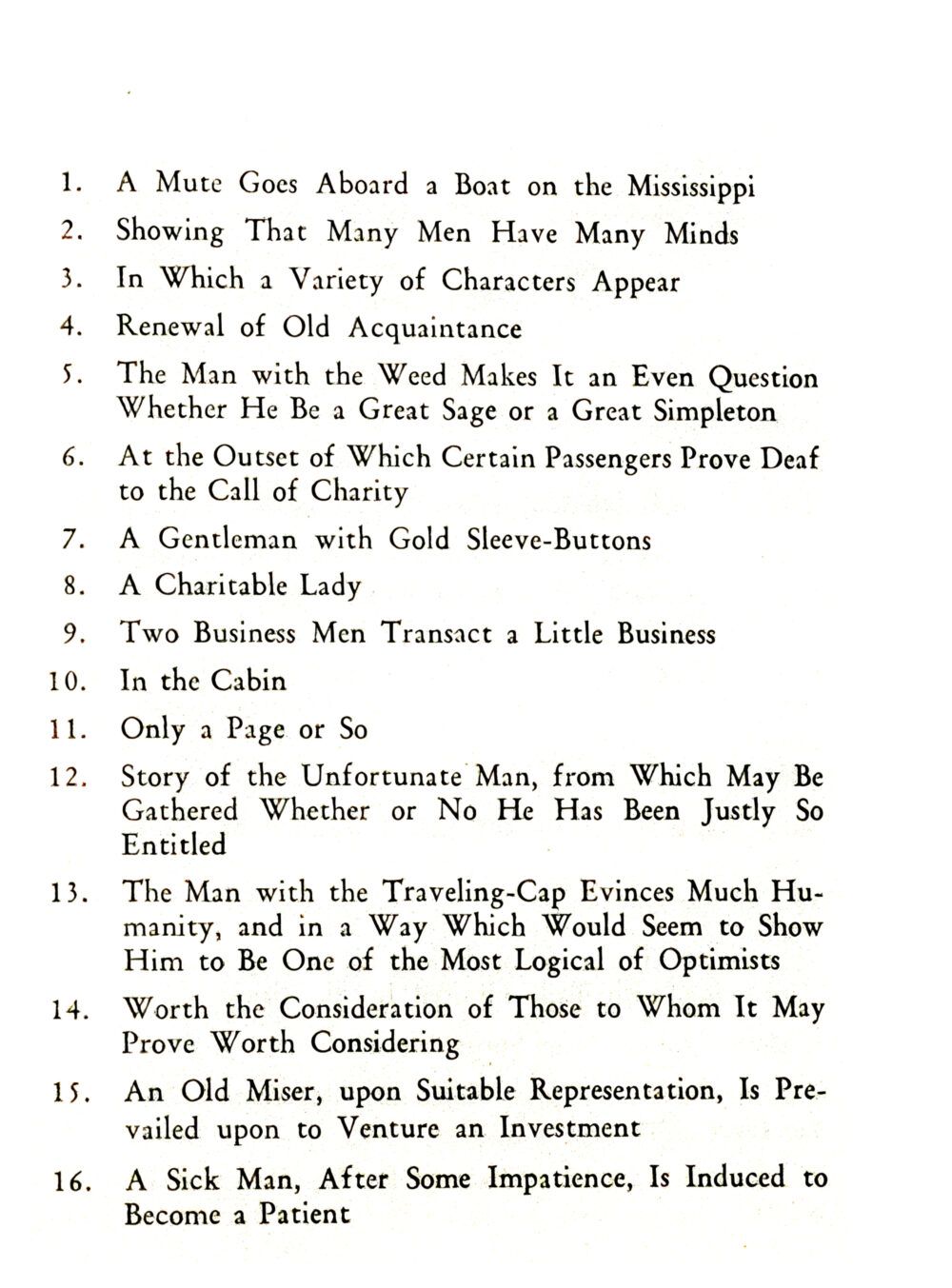

Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man

An adaption of Herman Melville’s final novella, possibly the project that made him lose faith in fiction. The script is based on the 1857 novel taking place amongst the transient community of a Mississippi passenger boat. The narrative arc consists of mysterious rises and falls in value and confidence, eyeing the role that economies, languages, gender, and media interfaces take in producing trust and showing how a trickster can interfere with them to produce something perhaps consoling or perhaps sinister, as the passengers cruise into an era without bearings.

But the example of many minds forever lost**

like undiscoverable Arctic explorers, amid those treacherous regions, warns us entirely away from them**

and we learn that it is not for us to follow the trail of truth too far**

since by so doing you entirely lose the directing compass of the mind**

For arrived at the Pole, to whose barrenness only it points **

there, the needle indifferently respects all points of the horizon alike.**

The Quick Brown Fox Jumps Over the Lazy Dog

A series of performance-viewings and cine-aerobics where groups simultaneously watch and mimic the gestures of a protagonist, shifting the attention from the action to reaction. Across multiple iterations this performance has gone into cold war thrillers, neo-realist dramas, fantasy and DW Griffith’s war reconstructions. A silver bullet, coming from the silver screen, is the only thing effective against werewolves, witches and other fairytale figures.

Thatcher & I

Interviews with actors who’ve played Margaret Thatcher in plays, TV and films, or who are interested in playing Thatcher. These interviewees talk about their lives from the perspective of Thatcher and Thatcher’s life as themself. The film takes techniques used to get “truthful performances” and repurposes them to explore the formation of beliefs and ideology.

The Owl

I am the owl**

watching over the forest at night**

I keep seeing, hearing, maybe even repeating**

at night everyone begins to repeat the past**

as if they might forget who they are**

I am the owl**

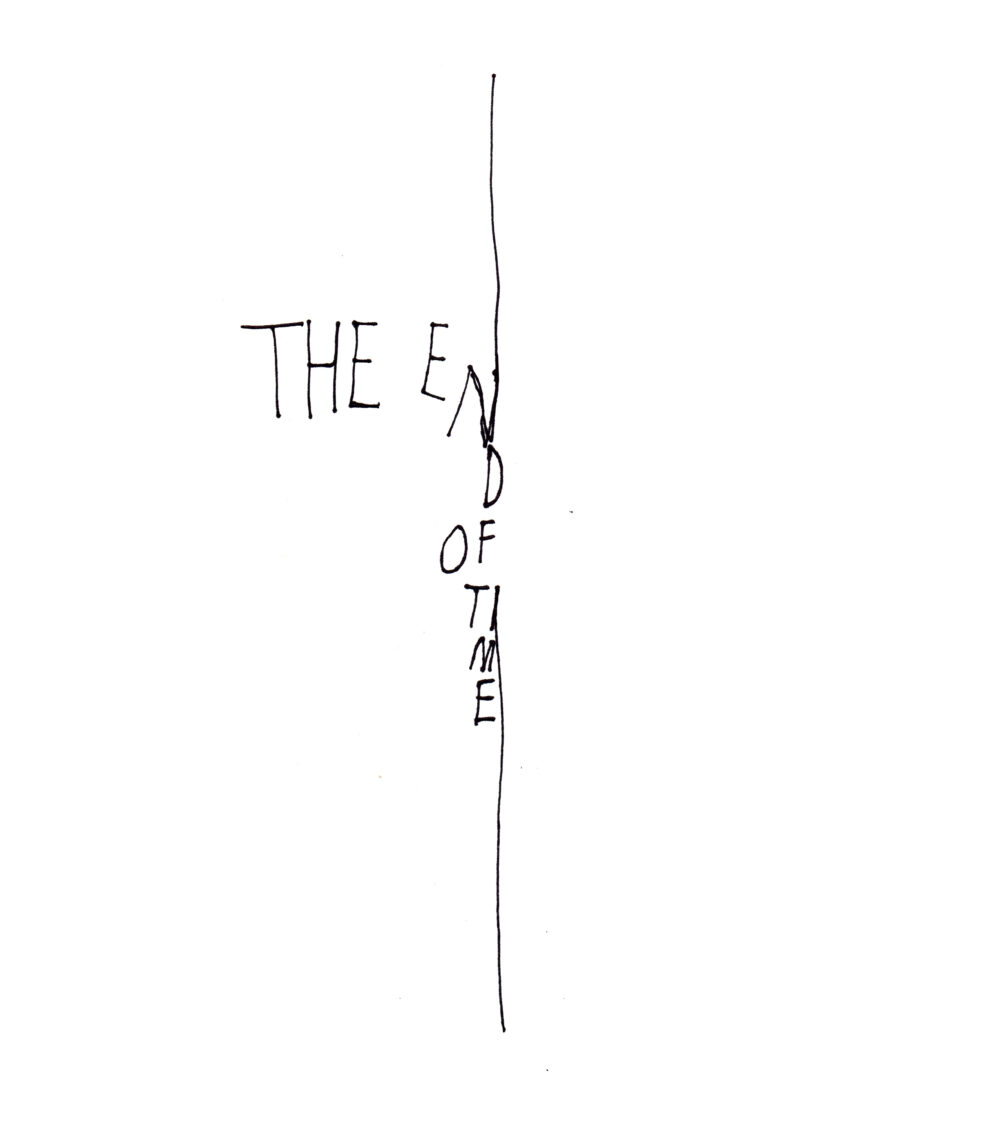

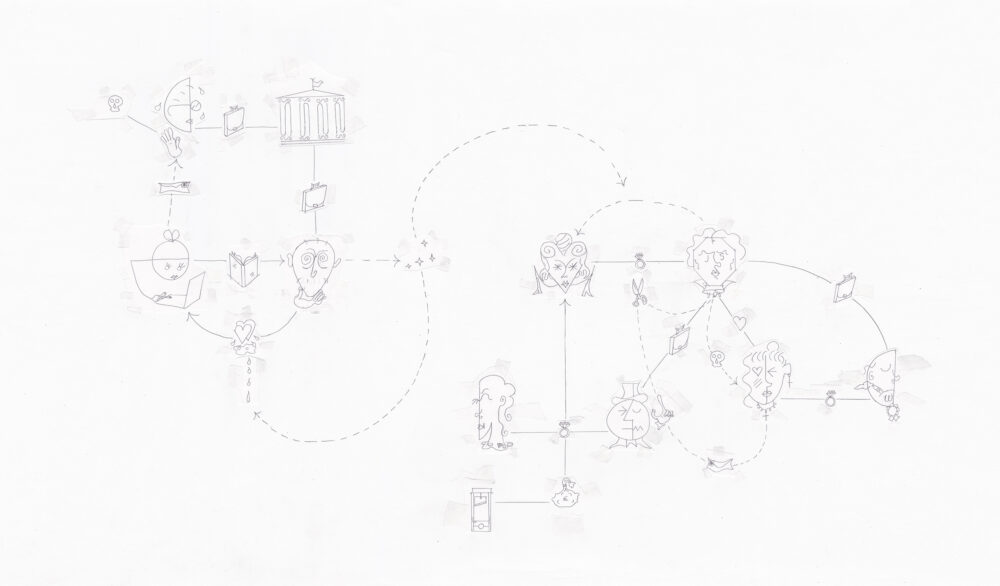

Plot

![]()

“Plotting” often means giving tension to a tale by arranging events, ** after the fact. **In a secondary definition, **“plotting” characters make monstrous or at least sinister-vibed schemes, ** in advance of the action. ** Together plots are themes “warped with various situational motifs… ** placed in tension like yarns on a loom before the weaving begins.” ** Like in a love triangle, plots make shapes and structure relations. **Yet because they get their momentum from lack **(of money, love, evidence, et cetera), ** this does not end well. **This DNA of doom travels through time, **from place to place, where “labyrinths of linkages reemerge in the same old place, **after the disintegration of old ways of life.” **3 Plots are spells, with actualizing effects, **and must be handled with care—or else! ** What follows are some cautionary tales, **about stories and life plotting against each other…**

On the right side of the diagram ** up the top is Mathilde de la Mole and Julien Sorel

characters from Stendhal’s novel The Red and the Black (1830) ** Julien is the handsome son of a carpenter who after landing a job with the local Mayor ** (bottom right) ** he seduces with the deeply religious mother of the family, Madame de Rênal. ** the rumours mean he has to leave ** but through his new connections he goes on to work for powerful Marquis de la Mole. ** and seduces the Marquis’ daughter Mathilde, ** for his personal advancement ** when their marriage is about to go ahead **

a letter from Madame de Rênal arrives, **addressed to the Mathilde’s father the Marquis. ** It calls Julien Sorel opportunistic, ** and between the lines calls Julien back to his old lover. **

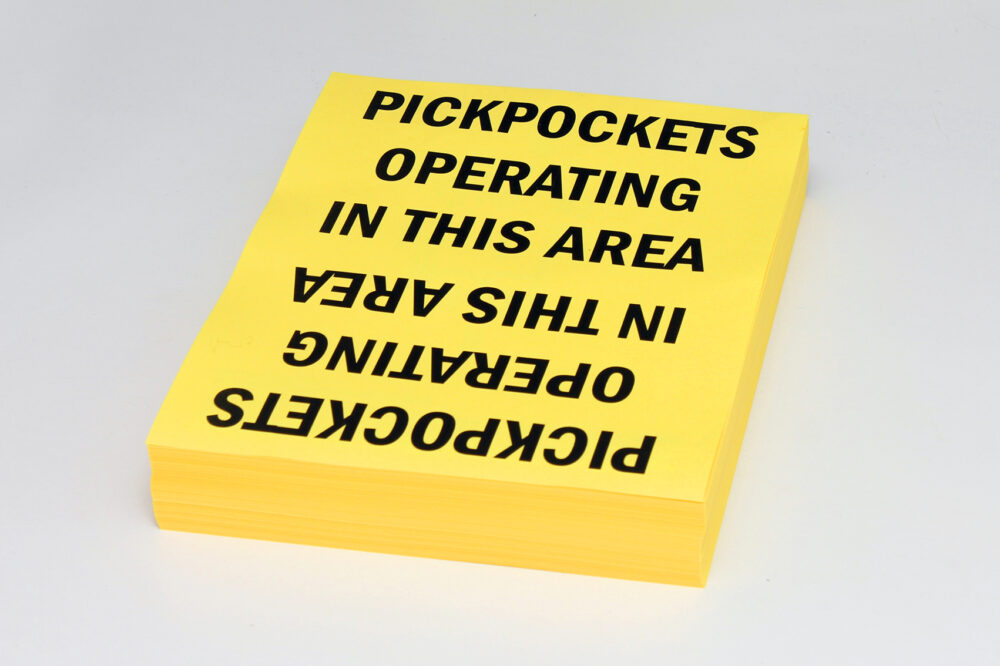

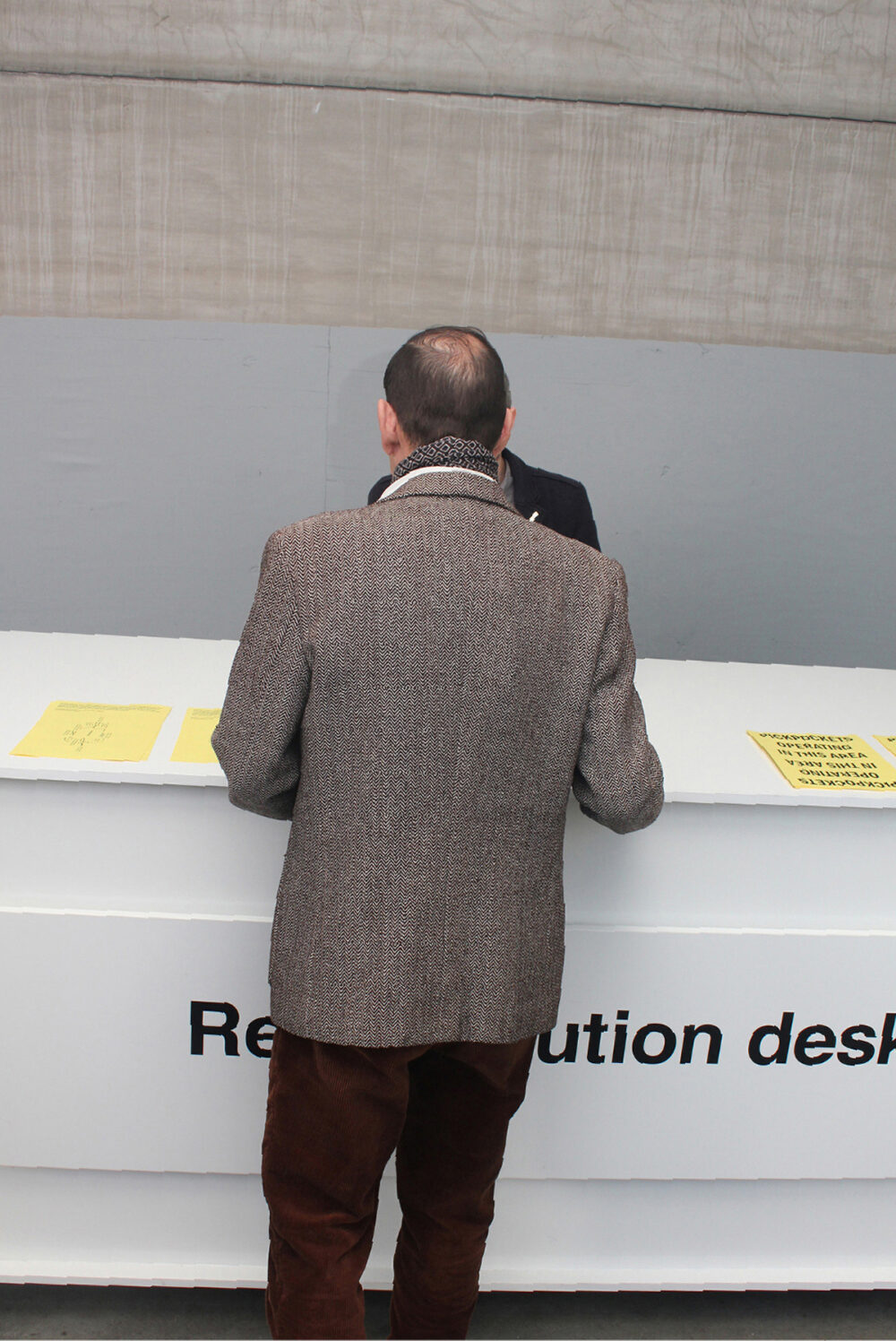

Pickpocket

Unidentified pickpockets moves throughout an art fair taking visitors’ wallets and purses. These are taken to a redistribution desk, where they are returned with a certificate of the exchange. Pickpocketing and business of the fair become lenses for viewing each other.

It's a little-known rule that we can only concentrate on one thing at a time. **

The jumpy pattern of our thoughts often gives us the illusion that we are aware of two thoughts simultaneously, **

but it is simply not true. **

That is why the “accidental” collision with the pickpocket goes almost unnoticed. **

Haven’t you experienced this “tunnel vision” at one time or another? **

Times when you are suddenly awakened from an almost dreamlike trance, to find yourself back in reality? **

This is the cover under which the pickpocket operates. **

In Victorian England, pickpocketing was declared a capital offence, and it was hoped that public executions would dissuade young and hopeful pickpockets. **

Scotland Yard soon abandoned this initiative when the spectators at these events complained of missing wallets and watches. **

If the mark is allowed to naturally take their mind off their wallet **

– if only for a few seconds ** seconds of death – **

they will be astonished to find that, without the slightest awareness, they have been robbed. **

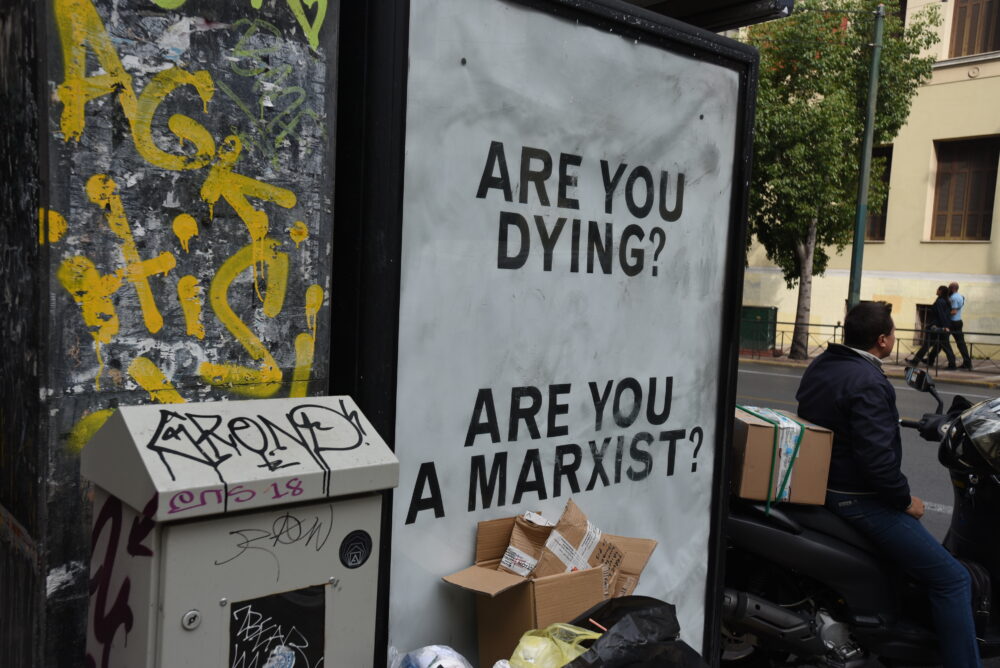

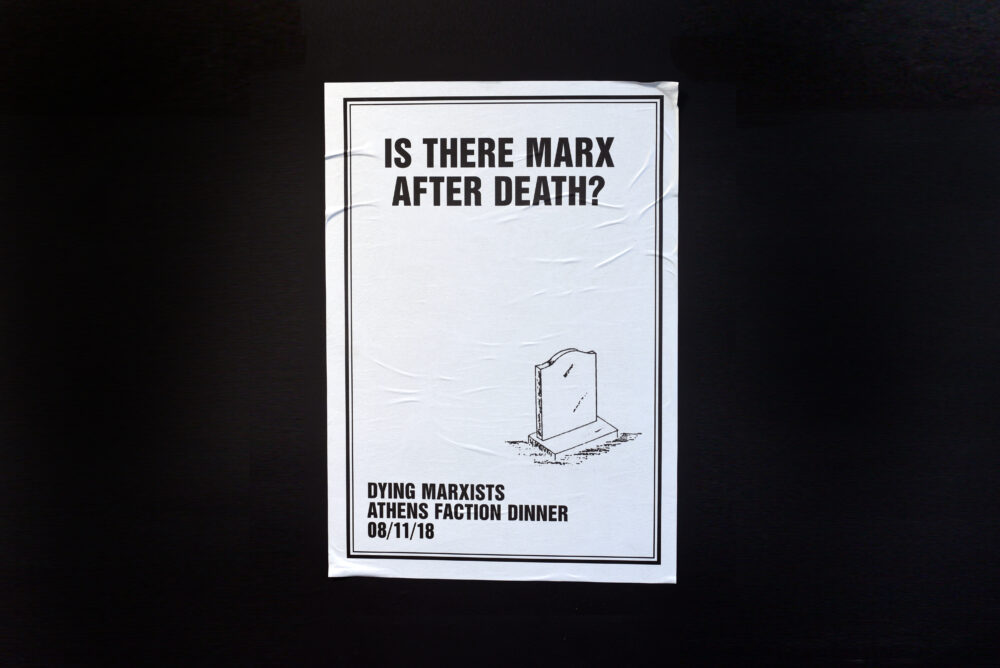

Dying Marxists

I first published a classified ad asking readers who considered themselves Marxists and were dying to get in touch. The project started to grow, becoming a documentary collection of interviews, a support group, and later a meme online, bringing together Marxists ranging from academics to dentists, students to the old and terminally ill. The discussions were around death through the lens of Marxism/Materialism, and Marxism through Death. In the Athens Biennale I created an outdoor ad campaign for Dying Marxists, leading to a dinner which was recorded via a journalist. The original ad asked people to take part in a documentary film, but in the event we decided to condense everything in this ‘film’ into a single frame. Pieces of discussion from the previous versions become the material in the next.

The most beautiful way of dying you find in the history of Marxism ** is the love letter of André Gorz. **

So he writes a novel-ish little book about his love to his wife, Doreen, ** when he is 83 and she is 83, **she is seriously ill, so she’s a Dying Marxist, ** and they commit suicide together ** so that none of them has to live without the other, **and it’s quite a moving book. **

The idea of consciously publicly committing suicide ** and to also publicly signal or to make public one’s commitment to one’s own love ** is quite beautiful.

The book was published a few weeks after.

RIP REBERT

Why would the most famous film critic of their generation post opinions anonymously in a distant corner of the Internet read here?

Museum Dreams

A fast story and a slow story start at the same time. **

The slow story did not delay, but began narrating immediately.**

The fast story, however, lay down to take a nap, confident in the speed of its narration. **

By the time the fast story arose and sped through to its final act, it noticed the slow story had already finished.**

CC

![]()

"One of the German words I've become more and more attached to in recent years is the word Zelle, or "cell." **

This word lets me imagine a large number of tiny spaces alive within my body. Each space contains a voice that is telling a story. **

For this reason these cells can be compared to cells of other sorts: telephone booths, and the spaces inhabited by prisoners and monks. **

It's beautiful when a phone booth is lit up at night on a dark street. **

In the section of Tokyo where I grew up, there was a park full of ginkgo trees. In one corner of the park Hood a phone booth that was very popular with young girls. **

From dusk to midnight it was continuously occupied. Probably the girls could develop their talent for telling stories better in this cell than at home with their parents.**

They gripped the receiver firmly and glanced around with lively, empty eyes, as if they could see the person they were talking to somewhere in the air.**

The transparent glass box, lit from within, where the girls spent so much time stood between the dark shapes of the trees in the park:**

this image fascinated me even then, when I myself was a girl. **

But the subject matter of the girls' conversations was of little interest. They spoke mostly about the males with whom they had relationships. **

Sometimes the phone booth resembled a transparent tree occupied by a tree spirit. **

The Japanese fairy tale "The Bamboo Princess" begins with an old man seeing a luminous bamboo trunk and chopping it down. **

Inside he discovers a newborn baby girl that he raises together with his wife.**

The tale ends with the girl, who has become a grown woman, flying back to where she really comes from: the moon.**

The nocturnal phone booth might also have been a spaceship that has just landed in the park. **

The moon men have sent a moon girl to Earth to inform them about our life. The girl is just making her first report. **

What would she say about the park? Would she have much to report so soon after her arrival? **

Later, in Austria, I saw a cell that immediately reminded me of the phone booth.**

It was made of solid wood and stood in the unlit corner of a Catholic church. **

The walls of the cell radiated warmth and calm; right away I thought I would be just as happy to stand inside telling stories as the girls in the phone booth.**

A friend told me the cell was called a "confessional" and that, like the nocturnal phone booth, it was a place to talk about sexual encounters.**

But unlike a modern phone booth, the confessional was made of wood and stood there like a tree whose roots have grown deep into the earth.**

It couldn't fly away like a spaceship. So there are storytelling cells that stay in one place, and others that appear to be mobile.**

And so I understood why a chamber that resembles a prison cell is better suited for composing an erotic text**

rather than a large room in which optical sensuality is staged.**

I don't think much of asceticism, nor do I believe that sensual pleasure can enter a piece of writing only when it is suppressed in real life. **

The claim that a person who writes is not truly living can be made only by someone who sees a person and his life as subject and object. **

He might say the most important thing is to live one's life.**

I would say: I live, and my life lives as well. Even my writing lives.**

Thus the question of whether a person is living when he writes is misguided to begin with.**

One asks this sort of question only to make everything revolve around man.**

It doesn't have anything to do with asceticism when someone sits in a cell and writes.**

It has much more to do with the activation of the living cells that comprise their own phone booths, monks' cells and prison cells within the body. **

Countless stories are told in these enclosed spaces. When I write, I try to hear the stories coming from within my body. **

When I listen, I realize how unfamiliar my own cells are to me. They consist of what I have inherited and what I have eaten.**

Thus it often happens that a story I hear within my body seems to me chronologically or geographically distant.**

But can one understand the language of cells at all? The question brings to mind the image of yet another cell: the booth for simultaneous interpreters.**

At international congresses you often see these beautiful transparent booths in which people stand telling stories: **

they translate, so actually they are retelling tales that already exist.**

The lip movements and gestures of each interpreter and the way each of them glances about as she speaks are so various

** it's difficult to believe they are all translating a single, shared text.**

And perhaps it isn't really a single, shared text after all, perhaps the translators, by translating, demonstrate that this text is really many texts at once.**

The human body, too, contains many booths in which translations are made. I suspect that these are all translations for which no original exists.**

There are people, though, who assume that everyone is given an original text at birth. They call the place in which these texts are stored a soul.**

In Hamburg-on-the-Elbe there is a small harbor known as Devil's Bridge.**

A long time ago, no one was able to build a bridge across the Elbe strong enough to withstand a severe autumn storm.**

The devil made the desperate Hamburg merchants an offer: he would build an indestructible bridge.**

In payment he demanded a soul. The merchants promised to give him a soul when the bridge was completed.**

When the devil had finished work, it became apparent that none of the merchants was prepared to forfeit his soul,**

and so they sent a rat across the bridge to the devil, who stamped on the rat in fury and then sank into the earth.**

Since then the harbor has been called Devil's Bridge.**

When I first heard this legend, I didn't understand it, because I didn't know rats have no souls.**

That is, rats have no souls for the devil, who is quite Christian in his orientation.**

In other religions that tell of the lives of plant souls and animal souls, a rat most certainly does have a soul- one every bit as precious as that of a Hamburg merchant. **

The devil needn't have been disappointed.**

I have two ways of visualizing the human soul. In the first, the soul looks like an elongated roll I once ate in Tübingen.**

This sort of bread is called Serle or "soul" in Swabia, and many people have souls in this shape.**

But this doesn't mean the soul is inserted into their bodies like a roll.**

The soul is an empty space in the body**

that must constantly be filled with the roll that has the same shape as this space, or with an embryo, or with the breath of love.**

Otherwise the owners of the souls feel as if something is missing.**

The second way I picture the soul is as a fish whose name is also "sole": thus the soul is related to water, or to the sea.**

I'm thinking of something like the soul of a shaman.**

Among the Tungus, for example, it's said the soul of the aspiring shaman draws the tribal river down to the dwelling place of the shaman's ancestral spirits.**

There, among the roots of the tribe's shamanic tree, lies the shaman's animal mother,**

who devours the soul of the new arrival and then gives birth to it in the form of an animal. **

This animal can be a quadruped, or it can be a bird or a fish; in any case, it functions as the shaman's double and guardian spirit.**

It's a nice thought that somewhere in the world the soul is leading its own life in animal form.**

The soul is independent from the person in question.**

The human being has no way of knowing what the soul is experiencing, but still there is a link between him and his soul.**

I would like to share a life with the person I call "my soul" as the shaman does with his:**

I never see or speak with this person, but everything I experience and write corresponds to this per son's life.**

I appear to be soulless because my soul is constantly in transit. In a book about Indians I once read that the soul cannot fly as fast as an airplane.**

Therefore one always loses one's soul on an airplane journey, and arrives at one's destination in a soulless state.**

Even the Trans-Siberian Railway travels more quickly than a soul can fly. The first time I came to Europe on the Trans-Siberian Railway, I lost my soul.**

When I boarded the train to go back, my soul was still on its way to Europe. I was unable to catch it.**

When I traveled to Europe once more, my soul was still making its way back to Japan.**

Later I flew back and forth so many times I no longer know where my soul is.**

In any case, this is a reason why travelers most often lack souls. And so tales of long journeys are always written without souls.**

According to Walter Benjamin, there are two kinds of storytellers:**

"When someone goes on a trip, he has something to tell about, goes the German saying,**

and people imagine the storyteller as someone who has come from afar. **

But they enjoy no less listening to the man who has stayed at home, making an honest living, and who knows the local tales and traditions.**

If one wants to picture these two groups through their archaic representatives, one is embod ied in the resident tiller of the soil, and the other in the trading seaman."**

There are some who travel much farther than sailors and remain in one place even longer than the oldest farmer: the dead. **

And so there are no storytellers more interesting than the dead. **

But it is a problem that their language cannot be understood, it is not even audible. How can one hear the stories of the dead?**

This is one of the most difficult tasks of literature and is solved in different ways in various cultures.**

A theater, for example, is often a place where the dead can speak.**

A simple example is found in Hamlet the dead father comes on stage and tells how he was killed by his brother.**

That is the decisive moment in this play, without which neither Hamlet nor the audience would have access to the past.**

They would have to go on believing the story of the murderer, who claimed Hamlet's father had been bitten by a poisonous snake.**

Through the dead man's story we learn a bit of the past that otherwise would have remained obscure.**

The theater is the place where knowledge not accessible to us becomes audible.**

In other places, we almost always hear only the tales of the living. **

They force their stories on us to justify themselves, and so that they will be able to go on living, like Hamlet's uncle.**

The tales told by the dead are fundamentally different, because their stories are not told to conceal their wounds.**

There are other places besides theaters where one can hear the stories of the dead: for example in an anthropological museum.**

At the Museum of Anthropology in Hamburg there are a number of transparent coffins lined up one beside the other, each containing a dead figure.**

Each figure personifies a tribe. A coffin standing on end resembles a phone booth because the figures inside look as if they are about to tell a story.**

That is probably why these coffins have to be standing up rather than lying flat, as coffins usually do.**

The figures in the coffins-dolls made of plastic-bear witness to the link between death and these dolls:**

all of the tribes represented in the form of dolls were, at some point in history, culturally or economically conquered by others and to some extent destroyed.**

As in other museums as well, a power relationship is illustrated here: that which is repre- sented is always something that has been destroyed.**

In a zoological museum, for example, a stuffed wolf might be put on display, whereas no wolf can display a human being.**

Historical museums, too, are marked by a hierarchical relationship between past and present.**

As long as an outsider appears threatening, the others try to destroy him. When he is dead, he can be lovingly represented as a doll in a museum.**

One can look at the doll, listen to the explanations of its way of life, view the photos of its homeland, but there is always something that remains unclear.**

There is a veil separating the museum visitor from the dead doll, making it impossible to learn much.**

One learns much more when one attempts to describe an imaginary tribe.**

What should their lives look like? How does their language function? What is this completely unfamiliar social system like?**

It is equally interesting to play the role of an observer who comes from a fictional culture.**

How would he describe "our" world? This is the endeavor of fictive ethnology, in which not the described but the describer is imaginary.**

I remember a day when I felt as though I'd heard the language of the dead.**

In 1982, in the spring, I visited a village in Nepal inhabited by Tibetans. Before me stood a temple from which a prayer was emanating.**

When I listened more closely, I realized it consisted of several voices.**

I looked inside the temple and saw a single monk praying. From his body came several voices. **

After he had taken a breath, he once more spread out a deep voice like a carpet on which several other voices could then appear.**

He produced these voices from within his body, offering a sounding board to storytellers who themselves had none.**

The dead, for example, who had no bodies of their own in which their voices could resonate, were able to become audible in the voice of the monk.**

At the time I tried to produce my own voice carpet.**

I failed in my attempt, but for the first time I became conscious of several secondary voices that form part of my speech.**

I began to pay attention to these voices as I spoke. Telling stories no longer took the place of listening; rather, listening gave rise to stories.**

Perhaps the ear is the organ of storytelling, not the mouth.**

Why else was the poison poured into the ear of Hamlet's father rather than his mouth?**

To cut off a person from the world, you must first destroy not his mouth but his ear."**

(From Storytellers Without Souls, by Yoko Tawada)**